Multibillion-dollar civic construction projects are usually bad news for wildlife, but after a new English underground railway line was completed, the upturned earth was used to rebuild a coastal habitat for birds in Essex.

The new bird sanctuary quickly became one of the best in Britain for avocets, spoonbills, black-tailed godwits, and other wading birds.

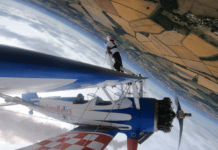

The Elizabeth Crossrail is a high-speed rail line that connects Reading in the west of London to Shenfield on the east coast. Seven million metric tons of soil were dug up during the $24 million project to make thirteen underground railway tunnels, half of which were transported by boat to the country’s eastern shore.

The earth was taken to Wallasea Island, which was once just a tiny peninsula of the wild Essex coastline with salt marshes, coastal lagoons, muddy flatlands, and other features, but it was drained several times during the Medieval period and after to make sheep pasture or farmland.

Farming is not always as profitable as it once was, and because the defensive seawall needed repairs, the farmer who used to own the land sold it to the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.

“Massive amounts of soil were dug up from below the streets of London during tunneling needed to create the Elizabeth line,” stated site manager of RSPB Wallasea Island, Rachel Fancy. “That material was given to the RSPB, allowing us to create our Jubilee Marsh, the cornerstone of our new reserve.”

In this case, the name Jubilee is appropriate. Bird-loving Guardian journalists reporting on the state of Wallasea Island now mention the diversity and abundance of species.

In the winter, hens and marsh harriers have appeared, while wigeon, teal, plover, yellow wagtail, lapwings, blackbirds, oystercatchers, and skylarks have all been seen in what has been described as a “nature lover’s paradise.”

It took 1,500 canal trips to bring the dirt to Wallasea. It was then transported via conveyor belt to a dump, where tipper trucks slowly deposited it along the shoreline to form a steady sloping terrain up from the sea, protecting it.

After the landscaping and manicuring were completed, the seawall was strategically compromised in three separate places at low tide, which gently partitioned the landscape into the various landscape features seen today, rather than turning it into a big muddy lake if the wall had been breached all at once at high tide.

Wallasea Nature Reserve hosted 150 breeding pairs of avocets, which are endangered in the UK, in its first year, instantly making it one of the bird’s strongholds.